I know an autonomous vehicle story has broken through to the mainstream when I get texts or emails from my parents and their friends making sure I’ve seen the story. Last week’s New York Times story was sent to me more than a dozen times by friends, family, former coworkers and distant acquaintances.

The story has it all, the torn-from-the-click-bait headline: Wielding Rocks and Knives, Arizonans Attack Self-Driving Cars, the man vs. machine narrative, tales of highly automated vehicles being ambushed and intimidated, and even a quote from a media theorist who wrote the aptly titled book Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus.

While the details were entertaining, the story drove home that we aren’t ready for “self-driving cars” … at least not as many people perceive and conceive them. The story featured quotes and examples of numerous Arizonans expressing suspicion (and even anger) over interacting with these new vehicles. This is a familiar response to a new technology that has outstripped public education and communication, leaving an information gap that’s quickly filled by misinformation, conjecture and hyperbole, not to mention, fear about what it can and can’t do, how it will be used, and ultimately, skepticism of how it can make lives easier, more enjoyable, and safer. While the term “luddite” wasn’t used to describe the attackers in the Arizona story, there are plenty of parallels to textile workers who destroyed machinery in English mills in the early 1800s using similar weapons. If you aren’t familiar with the story of the Luddites, I highly recommend the 20 minute Planet Money story about them.

What strikes me most about the fears and anger outlined in the story is how they reflect a similar sentiment I regularly hear when talking about my job: “self-driving cars” are coming, without the context of what broad societal benefits these vehicles can offer or perspective of how the technology is likely to be deployed in the near future. Sometimes the person I’m talking to is adamant they have no interest in the technology, others can’t wait for it to get here, but in both cases the timelines, use-cases, path to market, and scale show a fundamental lack of understanding and education about the technology at hand. Ultimately, this is a sign that AV stakeholders and promoters (automakers, tech companies, elected officials, departments of transportation, advocacy groups and academics alike) have a lot of work to do to explain what AVs can (and can’t do) and more importantly, why you might want them in your city.

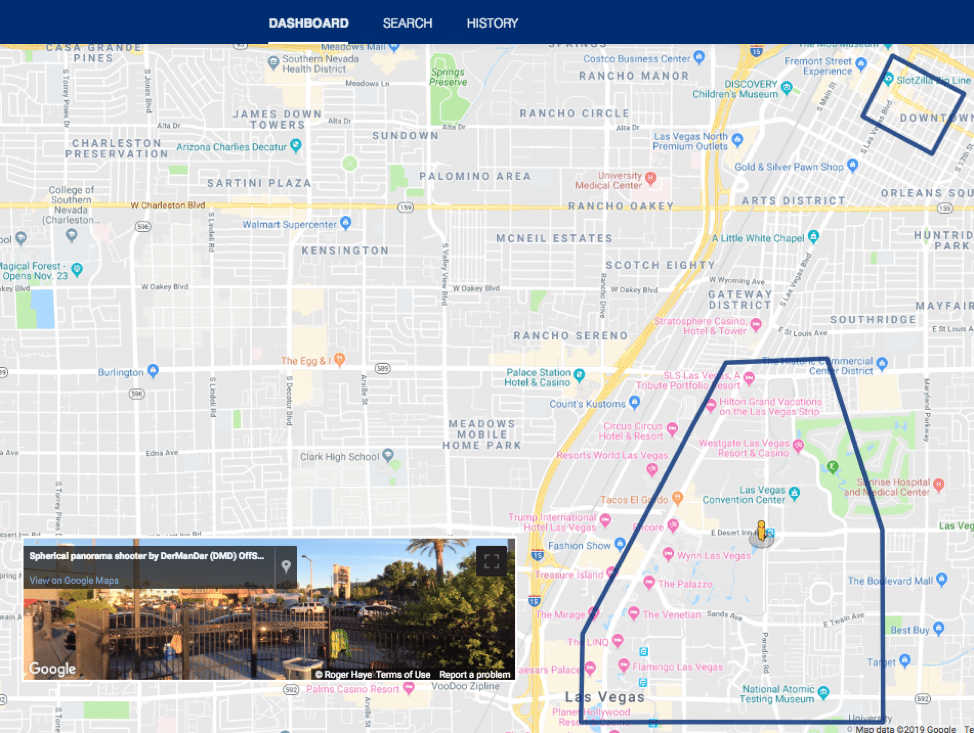

The most frequent concern I hear is that (pun intended) there’s no one at the wheel overseeing these vehicles: cars are believed to be operating on public roads without effective testing, oversight and public engagement. A clear public benefit hasn’t been outlined and cities have had few effective methods to demonstrate their active role in how AVs are successfully deployed. This changed six months ago when INRIX announced AV Road Rules, a platform that allows cities and road authorities to digitally fulfill their traditional role of setting and communicating traffic rules and restrictions. INRIX AV Road Rules offers a clear example of how a city or road authority is taking proactive steps to ensure AV safety and effectiveness. Today, Regional Transportation Commission of Southern Nevada (RTC) was the first city in the world to complete the digitization of two key testing grounds: Fremont Street in downtown Las Vegas and a new area surrounding the Convention Center. The data, input, confirmed and managed by the RTC is available to any vehicle operating on these roads and can be used to supplement existing HD maps used by AV operators.

For more than a century, physical signs and striping have been largely effective communicating the rules that apply to a roadway or intersection to human drivers. Relying on the techniques for automated driving systems have proved ineffective, particularly when there is the potential for these new vehicles is to follow the letter of the law at all times (unlike a human driver) … provided they have ground-truth data to work from, data only the associated road authority can provide. AV Road Rules marks an open tool that fills an essential data gap (ground truth traffic rules and restrictions) and, perhaps as importantly, a concrete step cities can take to show constituents they’re properly engaged with the deployment of AVs.

In the six months since AV Road Rules has launched, there’s been growing industry-wide agreement that consumer education and understanding of automated driving systems hasn’t kept pace with the technology. Public education is essential to prevent the misunderstanding, misuse, fear and backlash that could undermine the ultimate success of this technology (as seen in Arizona). Today also marks the most concrete and comprehensive step to address this challenge to date, with the announcement of Partners for Automated Vehicle Education (PAVE), a coalition of industry, nonprofit and academic institutions with one goal: to inform and educate the public and policymakers on AVs and the impact the technology will have on the future of mobility. PAVE members include AAA, Audi of America, Daimler, INRIX, Intel, National Safety Council, NVIDA, SAE International, Toyota, Volkswagen and Waymo, among others. The coalition is set to leverage the breath and expertise of its participants to structure public education and communication to counter the hyperbolic narratives (both heaven and hell scenarios) that have sprung up in the existing information vacuum.