Sitting in traffic congestion is costly, both in time and lost fuel. In our Global Traffic Scorecard, we estimate that congestion results in $81 billion, £9.5 billion, and €3.9 billion spent in lost time and fuel annually across the US, UK and Germany, respectfully, and many billions more when other countries are analyzed. While shocking, that doesn’t even include lost productivity, excess carbon emissions and the physical and life-stress that sitting in traffic jams can generate. While alleviating some of that pain through relieving traffic congestion is beneficial, a myriad of costs need to be taken into account prior to moving forward, along with policy, political and planning considerations.

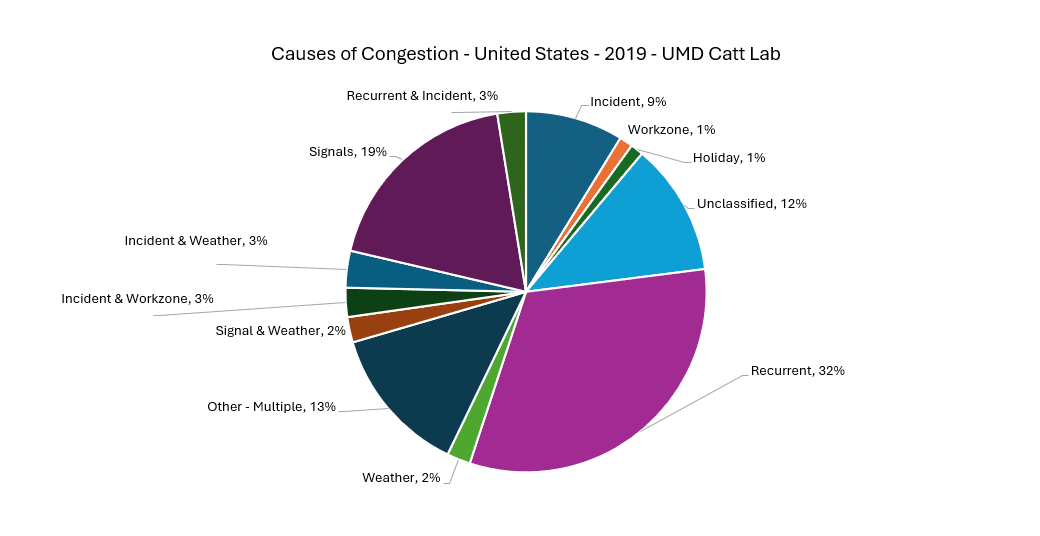

It’s important to know the sources of congestion as well. The University of Maryland’s CATT Lab breaks down the causes of congestion in 2019 in terms of vehicular hours of delay. The chart above reveals that about one-third of traffic congestion is from “recurring congestion,” a supply-demand imbalance on the roadway that results in almost daily traffic. Think congestion from commuting. Delay at traffic signals represent about one-fifth of congestion, while others, including incidents, weather, and multiple causes are responsible for the remainder.

Making roadway improvements to meet these specific causes is key to maximizing cost-benefit analyses and keeping people and goods moving.

Dealing with traffic congestion usually takes one of three different strategies:

• Congestion relief;

• Congestion mitigation;

• And congestion avoidance.

Congestion relief strategies aim to reduce the delay drivers and freight movers experience when traveling, reducing travel times. Congestion mitigation programs tend to focus on limiting the growth of traffic congestion, while avoidance strategies attempt to shift drivers to alternative modes of transport. While a specific transportation project may incorporate elements of each strategy, this blog will focus on congestion relief as the main goal.

Strategies:

1. Smart traffic signal timing. Active signal management is a supply- and demand-based strategy that allows DOTs to boost traffic throughput, the number of vehicles passing by a particular point, by making sure the signals better accommodate traffic demand. This increases throughput (and therefore, reduces congestion) by reducing split failures, improving arrival on green, and better managing turn movements. The advantage of smarter signal timing is the large cost-benefit ratio.

2. Smart parking/Curb management. According to our 2017 Parking Pain Report, the average driver in the U.S. spends about 17 hours per year searching for parking, resulting in $72 billion in lost time, excess fuel and carbon emitted. While the direct nexus between parking and congestion is still debated, drivers circling the block add vehicle miles traveled (VMT) to already-congested city streets. Making parking more available and accessible can reduce traffic congestion, but is impracticable and expensive in many instances. In general, there is vast support for the demand-side strategy of making parking “smarter” to increase turnover, however, there is continual debate on the supply-side, namely around whether to add on- and off-street capacity to meet demand. Opponents of adding parking capacity generally argue that it simply brings more cars into a dense, urban environment that is better accessible via other modes of transport.

5. Improve safety and incident response times. Reducing the number of collisions and improving incident clearing times can lessen traffic congestion and is a supply-side approach to cutting congestion – targeting “incident” related congestion noted by CATT Lab. If a collision occurs on a road, oftentimes resulting in the closing of shoulders and/or lanes, it reduces the available supply of road to meet demand. Safety approaches can include road modernization, adjusting speed limits, utilizing incident response teams, and a host of other projects to keep people and goods safely and effectively traversing the road network.

3. Road pricing. HOT lanes, express toll lanes, day of week/time of day pricing, and cordon tolling are all examples of road pricing – a demand-side approach to reducing “recurring” congestion. Simply put, this strategy prices lower value trips off the roadway, promising to reduce travel demand and increasing roadway efficiency. Supporters of congestion pricing generally approve of a “market approach” to this specific public good, while others want to reduce car use specifically. Opponents of pricing strategies often oppose the price itself or oppose pricing roads that were “already paid for.” Additionally, if imposed by a public agency, where spending is allocated may also gain or lose support.

1. Road expansion. Road expansion is a supply-side strategy to reduce traffic congestion by adding lanes to a roadway, modernizing freeway to freeway interchanges, and more. The additional road capacity is meant to accommodate traffic demand and typically targets “recurring” congestion. Road expansion may require additional right of way and are likely costly in dense, urban areas. Much of these costs can be avoided by strategically targeting bottlenecks that have large downstream effects on traffic. Other, cost-benefit friendly and “smarter” projects like hard shoulder running can also be explored. These changes are often welcomed by drivers, but opposed by groups that want to limit sprawl or car use for various reasons (housing density, environment, eminent domain).

While there are positives and negatives to nearly every transportation strategy to improve travel times for drivers, freight movers and emergency response vehicles, these changes must be taken in context to a local area or state’s specific goals, sources of congestion, and budget.

Though the COVID-19 pandemic significantly reduced congestion on U.S. roads for a few years, in many places traffic congestion already meets or exceeds pre-COVID levels while other modes of transport struggle to keep up. Strategically targeting specific areas of congestion can reap short-term and long-term benefits to a region’s population.